The Seeds of a Genocide

Can Woke ideology reach totalitarian status?

A few readers have contacted me about a recently released discussion between James Lindsay and Jordan Peterson. They cover ground related to my documentary, The Reformers, and Peterson creates space for James to sketch out his origin story. It’s a fascinating conversation that’s available on Dr Peterson’s YouTube channel.

Two readers have asked me to elaborate on the phrase “the seed of a genocide,” which James talks about in the clip below, so I thought I’d take some time with my reply and share it here.

One night during the hoax project, James called me to talk about peer review notes he’d received for the Progressive Stack paper. For those unfamiliar, the Progressive Stack is a technique used by Identitarians to prioritise the perspectives of "non-dominant groups". They do this by granting speaking privileges in meetings to people who have identities they consider most marginalised in wider society.

The Progressive Stack paper proposed ways to implement the stack in classrooms and expanded on the technique to effectively punish white, male, and heterosexual students for their perceived privilege.

The idea for the paper came up while James and I were joking about how identity scholars might go about indulging in vengeful cruelty while maintaining a dignified scholarly front. We landed on the idea of "experiential reparations", where groups seen as dominant would pay for the oppressions of their ancestors by being forced to experience them first-hand. James set out to see if he could bolster the concept with their existing literature and get it through peer review.

In part two of The Reformers, we talk about how the reviewers responded.

The paper's suggestions, things like belittling students and having them sit on the floor in chains, were so blatantly odd and inhumane that Jim felt he needed to justify them as acts of compassion. This was disapproved. Compassion, reviewers said, “recenters the needs of the privileged” and that the author should consult Megan Boler’s “pedagogy of discomfort” (learning by being made uncomfortable). The icy detachment of this comment sparked a long conversation about Identitarian psychology where the phrase, “seeds of a genocide" first came up.

Genocide is one of the most emotionally pregnant words in the English language. It conjures powerful images and sensations in anyone even vaguely familiar with the events of Stalin's Great Purge, the Holocaust, or the Cambodian killing fields. Mass-scale evil was repeatedly unleashed through the social engineering endeavours of totalitarian governments across the 20th century, and the spectre of that horror haunts our present-day political discourse. This spectre is both a useful guardrail in keeping us alert to warning signs and a manipulable fact of the political landscape.

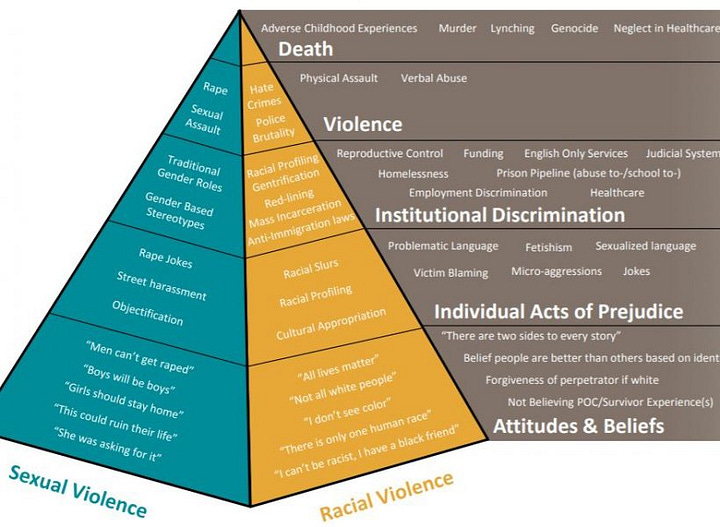

It’s common to see people leveraging these frightening historical precedents to bolster their political rhetoric. The ”Pyramid of Hate” is an example of this, where Identitarian diversity consultants summon the affective energies of genocide to disarm their audiences.

Things like “remaining apolitical” or saying “there are two sides to every story,” are apparently pavers laid down on the road to genocide. I’m not convinced.

I find myself stuck with the problem of being seriously concerned about totalitarian ideology and wanting to encourage vigilance without trivialising historical events or conjuring ghost stories about my political opponents. I think being specific helps, which is why I’m happy I have readers who are eager to understand exactly what I meant when I used the g-word. In the context of our “seeds of a genocide” conversation, James and I were referring to two specific aspects of the Identitarian movement that are also constituent elements of historic genocidal events.

The first is the goal for a civilisation-wide utopian enterprise (equity) that leans into the motivational power of grievance and revenge. They use a species of Orwellian doublespeak to wrap vengeful postures in words of fairness and recompense but the wrapping is thin and that eagerness we saw for experiential reparations is a recurring theme. The disjunct between word and action has a way of manifesting in absurd displays of passive aggression and anyone familiar with my work will have seen many examples of this.

The second is an inability to empathise with the suffering of their out-group. I define the Identitarian in-group as non-normative, or “intersectional” identities, and the out-group as normative, or “privileged” identities. They seem to have a hypersensitivity to what they theorise as the needs of their in-group and a cold indifference to the struggles of those they deem “privileged”. This was on display in the peer review notes and another recurring theme in the movement more broadly.

These two characteristics - grand-scale social engineering with an undercurrent of revenge, and hypersensitivity to in-group victimisation with cold indifference to the out-group - can realistically be seen as seeds of something very dark and dangerous. But those seeds are just seeds and they will need to find fertile ground to flourish. I’m not convinced they have that.

Over the last few years, I’ve learned a lot more about the movement and have come to see the Identitarians as an influential sect within a much broader technocratic elite. Their goals are morally fashionable in powerful circles but I don’t think they alone have the appeal or cohesive ideological framework to form a totalitarian regime, let alone a genocidal one.

“Equity”, the social engineering project at the heart of the Identitarian movement, is an administered social environment in which privilege is redistributed to make citizens equal. Perhaps the most concerning part of this is that they conceive of "privilege" as something deeply embedded in the subconscious minds of a given population. For the Identitarian, inequality follows from the way people are culturally conditioned to perceive certain groups, and so if perceptions can be re-engineered at a mass scale then material inequalities will take care of themselves.

I use the word “re-engineered” here because they’re not focused on consulting volitional conscious minds in an attempt to change them. They see human beings as programmable nodes determined by cultural forces. This leads to the circumvention of liberal democratic modes of persuasion and a focus shift to epistemological supply chains where they seek to engineer culture at its source.

This is why much of their activism revolves around pedagogy, the academic term for “theories of education”.

They strive to manipulate consciousness at a mass scale by changing the way we educate fledgeling minds, and converting our shared media of consciousness - language, art, literature, and knowledge - into a kind of technology that they believe will produce “equity”.

To seek control of art, history, and culture for use as a means to a utopian end is yet another characteristic the Identitarians share with totalitarian regimes. For instance, Stalin referred to cultural workers as “engineers of the human soul”, and artists faced intense political scrutiny and persecution during China's Cultural Revolution. However, their obsessive focus on perception dissociates their enterprise from the material world. I see this as a barrier to their reaching totalitarian status, despite the worryingly powerful influence of their ideology on our institutions.

In my opinion, the Identitarians are a force of deconstruction and decay rather than adherents of a belief system capable of exerting complete authority. If they do start accumulating a body count, my guess is it will be due to deaths of despair and incompetence rather than a concerted genocidal effort.

Orwell famously said, "‘If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – for ever.’".

I would rephrase that today as, "‘If you want a picture of the future, imagine fingernails scraping down a chalkboard – for ever."

When the Soviets took over Kazakhstan, they began searching for the bourgeoisie and proletariate. Unfortunately for them, Kazakhs were primarily hunter/gatherers. So, they didn't have obvious owners and workers like the industrial societies Marx was writing about. "No matter! We'll just say those with historical wealth are the owners (or "bai"), and those without are the innocent proletariate."

Unfortunately, if you look back far enough - everyone - has some historical wealth. So, anyone could be persecuted. The same is happening here. If you create some amorphous historical guilt, you can justify anything, and persecute anyone. 1.5 million people starved or died from internal repression in Kazakhstan. Let's not do this again.