A Born Gentleman

R.I.P. Marc Jacques Serge Gerard Nayna

My father died recently. I’ve been trying to steer my mind back to work, but my thoughts keep drifting in his direction. I may as well tack into the headwind and write about him. He was the most productive person I’ve ever met, so it seems fitting to honour him this way.

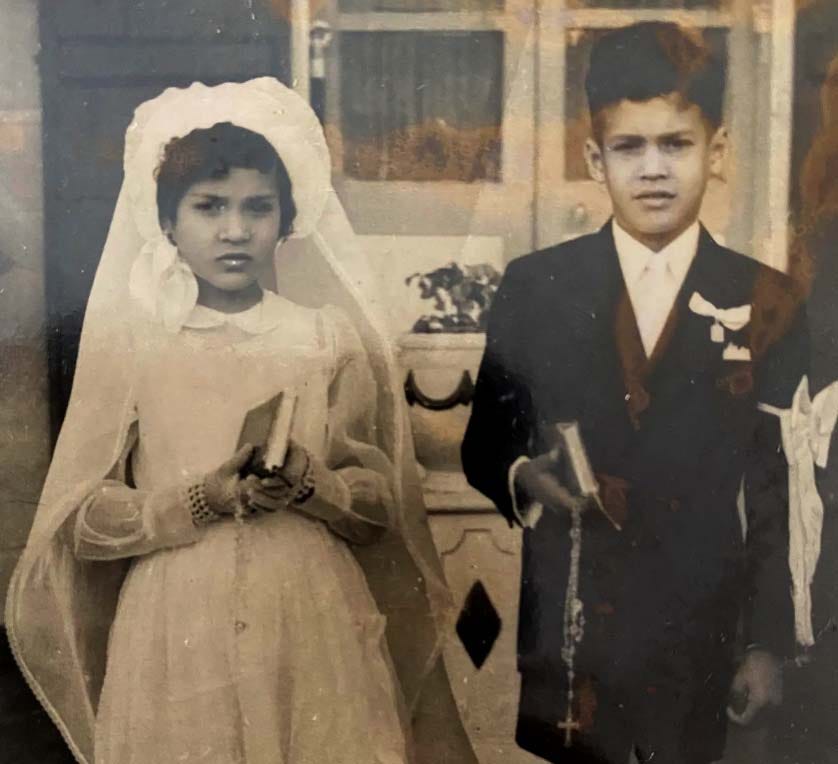

My father’s name was Marc Jacques Serge Gerard Nayna, but he went by ‘Serge’ and insisted his children call him ‘Papa’ to carry our French Creole legacy. He was born in Port Louis, Mauritius, eight hours after his twin sister, Josiane, and he used to joke that he let his sister go first because he was a born gentleman. By all accounts of his life, it was an honest quip.

He grew up with very little but reminisced about his early life with a smile. He spoke of “living in his imagination” through warm island days. He played soccer with his brothers, plucked seafood fresh from the ocean, and birds he caught with homemade glue (don't ask). On rare occasions, he would divulge the difficulties of island poverty. His younger brother was left permanently disabled after a brush with meningitis, and his father couldn’t afford treatment for a chronic illness, which hung heavy on his household. These experiences likely fertilised the ground from which his ambition grew - a quality that would define his life.

As a boy, he worked several jobs while diligently studying, earning himself a sought-after position in the island’s largest bank. There, he joined the cycling team and dominated Mauritius’s cross-country championships. He won three consecutive years, earning himself a reputation as the island’s "athlete-banker."

As his teenage years came to an end, so did the colonial rule of Mauritius. For you to understand this part of my father's story, I’ll need to digress into a brief history lesson - bear with me. The island of Mauritius spent most of its existence as an uninhabited speck in the Indian Ocean until the French set up its first enduring settlement in 1710. They imported around 60,000 slaves from Madagascar and Africa to establish a naval base and plantations in the island’s volcanic soil. Mauritian ‘Creoles’, which Papa translated as ‘mixed-bloods,’ trace their lineage back to the slaves and plantation owners of this era.

During the Napoleonic Wars, Mauritius functioned as a French stronghold for raids on British ships until their provocation led to a strong expedition to capture the island.

A Catholic Franco-Mauritian elite retained control of the island's large sugar plantations and was influential in both business and banking under British rule. This group forged a strong alliance with the Creole population, who shared their Catholic faith.

In 1835, the British abolished slavery and began importing indentured labourers from China and India to expand the plantation economy. Over time, the Hindu and Muslim Indian populations came to dominate the island’s ethnic makeup, and political power gradually shifted from the Franco-Mauritians and their Creole allies to the Indo-Mauritian majority. This laid the foundations for the identity politics that shape the island today.

Papa was born into the Creole minority, though our family name, ‘Nayna,’ suggests a Montague/Capulet-style story of intermingling somewhere along the family line. Even so, Papa was a devout Catholic and a Francophile, seeing himself in the French elite with whom he partially shared bloodlines.

The British started the process of pulling out of Mauritius in the late ’60s, and a looming power vacuum raised the temperature of ethnic tensions until they boiled over into riots, rapes, fires, murders, and looting.

When the bank offered Papa a promotion to work and study in Nairobi, he faced a dilemma - take the bird in his hand and leave his family on the fractured island or start anew together in a country with better prospects.

He once told me I should thank both God and John Maynard Keynes for my existence because his decision to immigrate to Australia was based on a Keynesian comparative analysis of the planet. At the time, the two most appealing options were Canada and Australia because of their abundant natural resources and limited internal competition. Ultimately, he ruled out Canada - “too cold for me.”

Decolonisation, civil rights, and multiculturalism were sweeping the globe, and elite Western opinion was sharply turning against racialist policies. Australia had begun dismantling its long-standing Immigration Restriction Act (1901), known as the ‘White Australia policy’, which aimed to heavily restrict numbers of non-white migrants to Australia and expedite the deportation of undesirables.

This made it possible for Papa, his two sisters, three brothers, and their parents to immigrate to Sydney, albeit with more difficulty than European immigrants at the time. He told me about a long moment shared with an English immigrant, who mentioned that his passage had only cost £10. Papa explained how the Nayna family had pooled their savings and borrowed from their local parish to afford the trip, and the two stood silently contemplating what it meant.

Papa experienced real racism in Australia, not the socially neurotic kind studied in contemporary academia. He never dwelled on it, though, as a matter of pragmatism because he knew that complaining did little to improve material conditions. If I ever brought him my social grievances, he would cite endless examples of people destroying their lives in pursuit of redress. He practised a Christian stoicism - we should accept the cards we are dealt and strive for the good, the true, and the beautiful wherever we can find them. All else is self-mutilation. It wasn’t perfect, but on the whole, Australia was a welcoming place with far less ethnic friction than the country he left behind.

When they arrived at their first lodgings in the red-light district of Sydney, my Grandmère famously said, “Don’t unpack your bags. We’re not staying here.” The family slept three to a bed, a fact all the more horrifying if you’ve experienced my disabled uncle's relentless gas. Nonetheless, Papa was steadfast. He thought long-term and was confident that, with time, they would build a better life.

“Michael, there was gold in the streets…” he said about the opportunities available in the booming country, “… and the Australians were too drunk to pick it up.” He respected his hosts but could never understand the heavy drinking culture, which, for the boomer generation, can only be described as a bafflingly functional alcoholism.

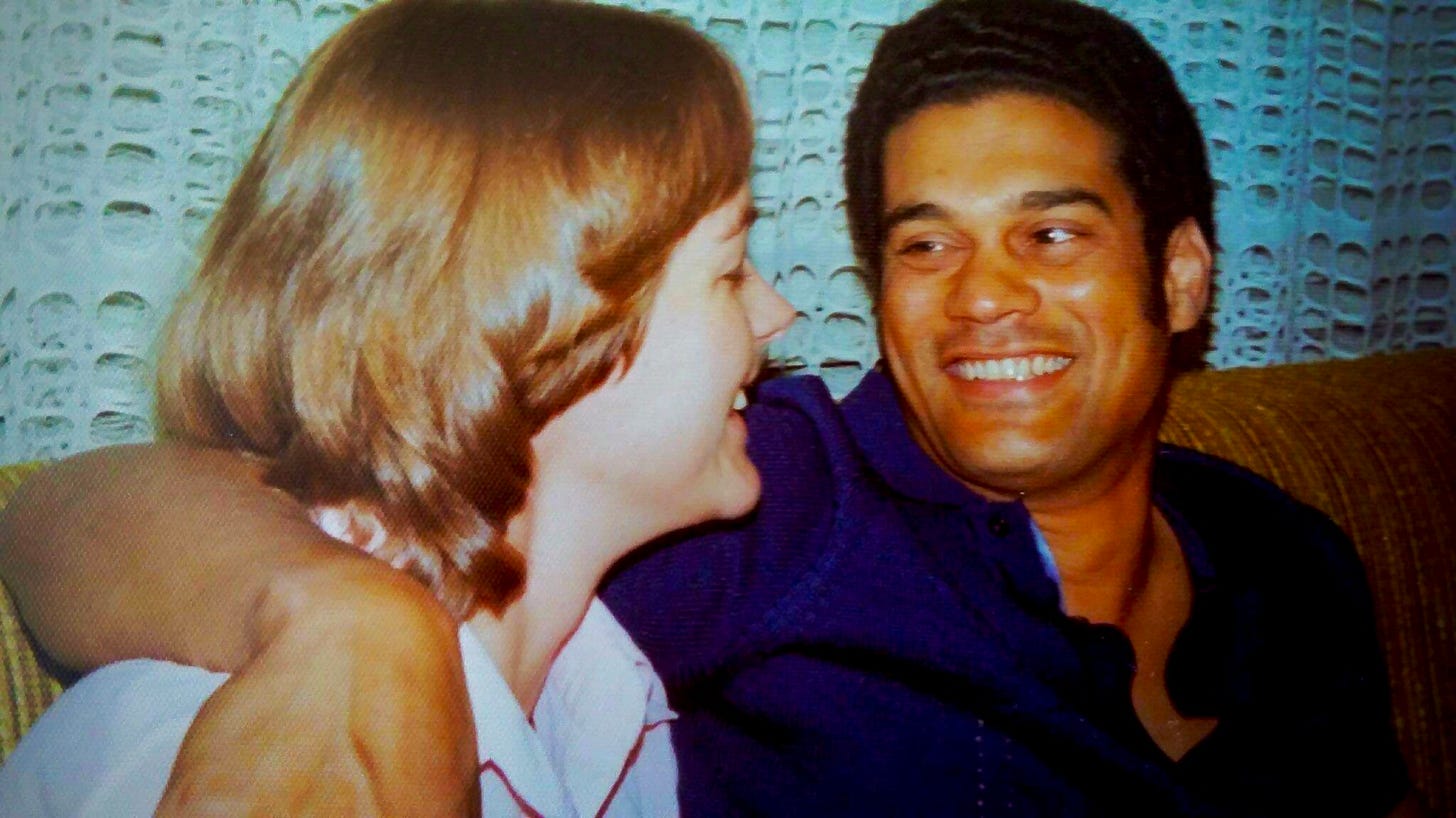

Despite being a handsome man, Papa never had much luck with women. He told me that changed with the shifting zeitgeist of the ’70s. He recalled an Australian woman who pursued him aggressively, taking him to a screening of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner - a film about a young white lady introducing her African American fiancé to her liberal yet conflicted parents. After the movie, she invited Papa to meet her own parents, and it dawned on him that he’d been cast as Sidney Poitier in her not-so-subtle progressive fantasy. He found it all very amusing and told the story with a bewildered grin.

Papa sometimes spoke of feeling out of place, as though he belonged to another time. He struggled to connect socially with anyone outside his family until he met Mum, Maree Jacoba Bruin – a Netherlands-born nurse who, despite assimilating more smoothly than Papa, remained somewhat on the fringes of mainstream Australia. He said it was different with Mum because they shared the same values and, as devout Catholics, a similar culture. I’m sure it helped that she was also beautiful.

Mum inherited a shrewd pragmatism from being Dutch and growing up on a farm, and combined with Papa's relentless work ethic, they made a formidable team. They had four girls in quick succession - the eldest, Ann Marie; twins Roselyne and Patricia; and Danielle, a quiet but cheeky girl who exited the womb with a mighty Mauritian bouffant.

Papa began his Australian career in an entry-level role at the ANZ Bank. As family lore has it, he walked in on an Italian colleague swearing loudly in his native tongue, furious after failing the bar exam. Papa paused for a moment, sensing an opportunity, and asked, as if he were pulling a block from a precarious Jenga stack, if he could borrow the books to try his luck. The fiery Italian scoffed, shoving the books toward him before storming off.

Papa took the books home and studied law in the car after work, while Mum stayed in the house with four little girls, all under the age of four. He passed the exams and moved to Melbourne to become a lawyer for the bank while moonlighting a solicitor’s practice from his home office.

He loved the law. In particular, English common law because it’s based on the principle of stare decisis, meaning courts follow decisions made in previous cases with similar facts. He appreciated the elegance of a legal procedure that matured over time, with judges passing down a body of judicial wisdom to future generations. It’s very Catholic to have reverence for institutional wisdom, and he liked being part of something that conferred dignity. I also believe his experience of the chaos that unfolded after the English departed his island made him value the stability and benevolent impartiality he saw in the Australian legal system.

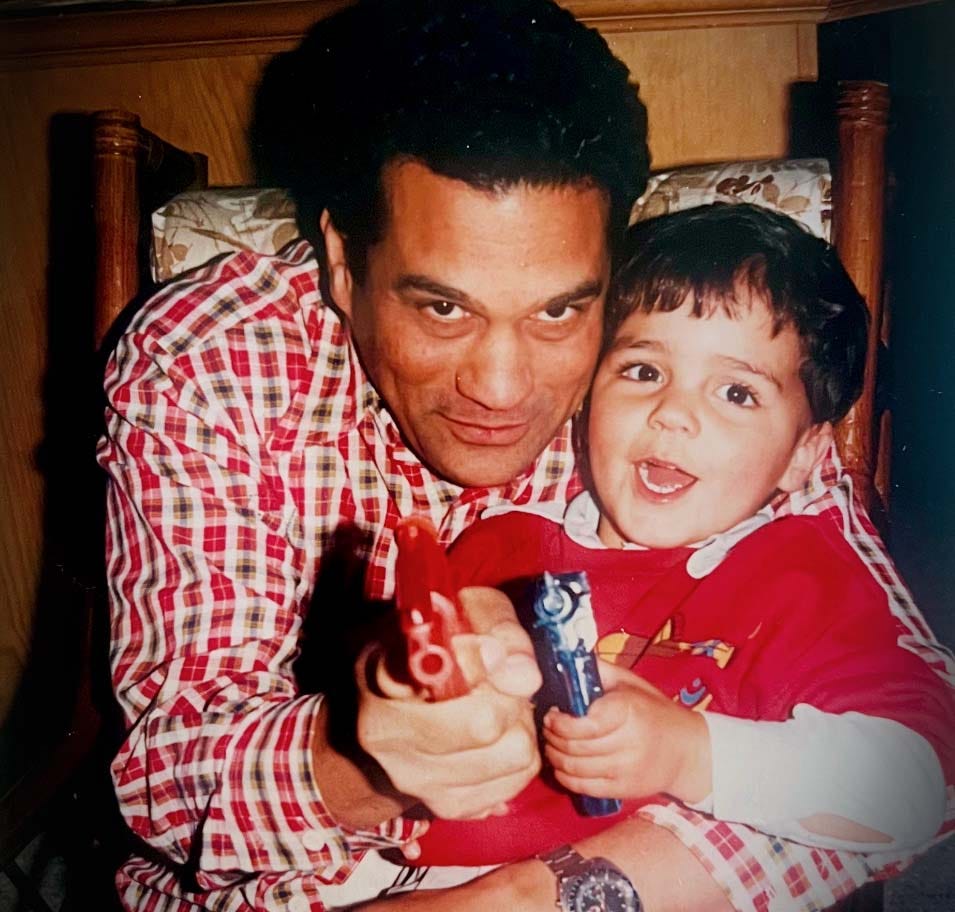

Soon after the family arrived in Melbourne, I was born, followed by my younger brothers, Matthew and Christopher. As a child, I knew my father as a distant, work-obsessed disciplinarian. I remember stealing moments from him by climbing into his lap during his nightly routine of watching the SBS World News. His veins were hyper-vascular, like soft worms beneath his skin, and I would press them down to watch them spring back with a spellbound curiosity. The dank smell of Victoria Bitter beer lingered in the air as he shook salted peanuts like dice, flicking them one by one into his mouth from a distance.

He was the kind of immigrant people refer to when they promote migration. Through extreme sacrifice, he put seven children through private education, selflessly served his parish and community, supported charities, and offered legal support to families in need. I recall drunks calling the house in the small hours of the morning and distressed-looking people regularly showing up on our doorstep asking if they could speak to Serge.

Throughout my life, I watched my parents claim their place in the birthright of all hard-working Australian boomers. When I was small, we lived simply. Rice and potato-heavy dishes kept the nine of us fed. By my teens, meat had become a staple. Now, we gather in restaurants. It feels strange, like stepping into a life that isn’t ours. Papa felt that most. He always ordered the cheapest item on the menu, though he no longer needed to.

About ten years ago Papa had his first bout with cancer. He beat it, and the fight knocked him into a contemplative phase of life. He softened his tireless work ethic and spent time cultivating an appreciation for his rapidly reproducing family. He studied theology at the tertiary level, which branched into DIY studies of philosophy. Whenever I was in town, he’d schedule regular dinners to discuss his latest intellectual project - Unravelling the works of Hegel, Descartes, or Friedrich Nietzsche.

It was during this ten-year reprieve between the cancers that I grew to understand him, and him me. Given I’m a dissident creative and he was a lawyer who revered institutions, it took time. We’d lived under the impression that we were completely different people, but we discovered I’m more like a clone born into radically different conditions.

Last year we learned the cancer had returned. In the bar-fighting days of my misspent youth, if a Lebanese lad threatened to call his cousins it was a serious matter. This time, the CT scans showed that the cancer had summoned several carloads, and the diagnosis was terminal.

My fiancée and I left the UK to live with him while he fought. I cherish the time, and if there’s one lesson I can impart from the experience, it’s this - go toward someone who’s on their way out. My natural impulse was to recoil, which is common, I think, and your mind will normalise the process by reducing its gravity. But if you can face the painful reality head-on and give it the weight it deserves, the person facing death will feel less alone, and you won’t be left with regret.

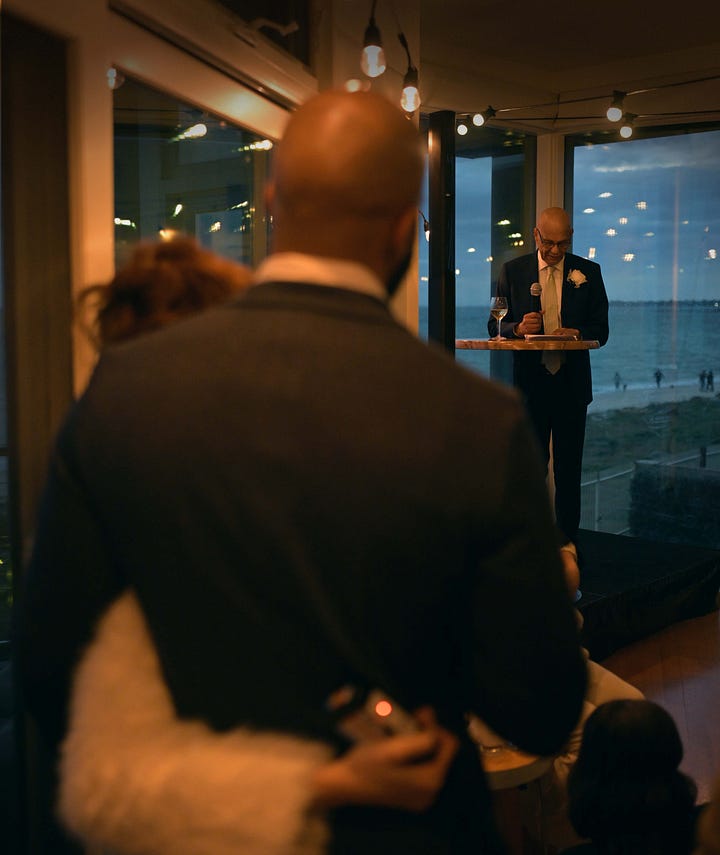

We sped up our wedding plans, and he held the cancer at bay to attend.

His health deteriorated quickly after the wedding, and his final days in the hospital were spent surrounded by the large immediate family he created. There were more Naynas than nurses, and several of us were nurses. We took shifts so he was never left alone. We shared stories, played music, held his hand, swabbed his mouth with whisky, and expressed our love and gratitude for him.

Since his first job selling tickets to the race track in Mauritius, Papa had loved horse racing. Drawn to the mix of chance and strategy. The Melbourne Cup is a major event on the Australian calendar, and a few days before the race, my brother Matthew asked Papa for a tip. In a semi-conscious state he mumbled two words - “Number eleven.” The odds were long, 151 to 1, but we placed a bet.

Papa passed away on the morning of the race. Later that day, number eleven, a rank outsider, won the Melbourne Cup.

I’ve been turning the event over in my mind, searching for a rational explanation. Nothing satisfies. I’ve come to think of it as his last move. He was a man of abiding faith who had worked hard to challenge the materialist constraints of my modern mind. It’s exactly the kind of seed of doubt he would plant before stepping over to the other side.

Well played, Papa, I’ll take it into consideration.

A great tribute to a great man, Serge would be very proud of this

My mum doesn’t have Substack but asked if I could comment for her

“That’s absolutely beautiful. Thank you for writing it, Michael. How remarkable No 11 win the Melbourne Cup and he passed that day. Divine intervention.”