The Digital Reformation

A Civilisational Convulsion

Sanctuaries of Meaning

In a 1996 presidential briefing, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan compared the economic activity of the early internet to the discovery of a new planet. At the time, the administration was watching what later became known as the dot-com bubble. A few years later the bubble burst and fortunes vanished, but Greenspan’s cyber planet held its shape.

By most estimates the internet economy now grows at more than twice the pace of the physical one. The world’s factories, warehouses, ports, and farms still matter, but atoms don’t move like bits, and much faster expansion is happening somewhere you can’t point to on a map.

Thinking of the Internet as an abstract planet has always struck me as a fruitful way to view the sprawling technology. When I was in the business of building social media platforms, I found that giving the Internet a sense of place helped me to hold unfamiliar tech concepts together and communicate strategies to my collaborators. I thought of my co-founders as explorers and our developers as tradesmen as we carved out a piece of land from the limitless cybermass and built on it. We established laws through code, shaped customs through the user interface, and encouraged digital pioneers to build profiles on our land in the hope that one day, we would preside over our own digital nation.

The playful construct became more profound for me when I came across philosopher Karl Popper’s concept of the ‘Three Worlds’.

Popper wrote about three distinct “Worlds,” which he used as a categorical schema to think about reality as a whole. World One, he said, is the realm of physical objects, the lifeless domain of matter and movement. This world gives rise to living organisms from which a separate world of subjective states emerges. The second world is the realm of experience, where all feelings, inner thoughts, and memories reside. From the subjective realm of World Two, a separate world of human abstraction is possible - this is our intersubjective “World Three”.

Popper’s World Three is a category that includes our ever-evolving language, art, culture, and concepts. It’s our collective world of meaning that’s not quite physical, although it manifests through material means, and it’s not entirely experiential, though it’s felt in our experiences. It has existed in various forms for as long as humans have communicated and our civilisations are built and destroyed via World Three’s many configurations.

At any point in time, a massive corpus of human mental activity sits scattered across the planet within minds and media, ready to be engaged with. This sprawling mess of symbolised thought is created and destroyed, lost and rediscovered, built upon and reconfigured as human populations work together to create meaning and commune through it.

Human groups will organically arrange symbolic sanctuaries of meaning that form the basis for collaboration and community. Put another way, a sanctuary of meaning is a complex of facts, values, and stories that represent the world, allowing people to place themselves within a coherent context.

Sociologist Clifford Geertz, borrowing a line from Max Weber, wrote that man is “an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun”. I suspect Geertz and Weber chose the spider-web analogy because the web is not under the spider’s rational control. It emerges naturally, shaped by environment as much as the instinctual information is embedded in the spider. Our communal web is also not under our rational control, even though we can rationally contribute to it.

The Reformation

Early humans transmitted their tribal sanctuaries verbally, which put hard limits on how much complexity could be memorised and shared. The discovery of writing systems was a quantum leap in information storage and transmission. Humans externalised memory into physical matter, and gained the ability to think more clearly across time and space. As we got better at learning from the dead, teaching the unborn, and converging on shared symbols, tribes expanded into civilisations.

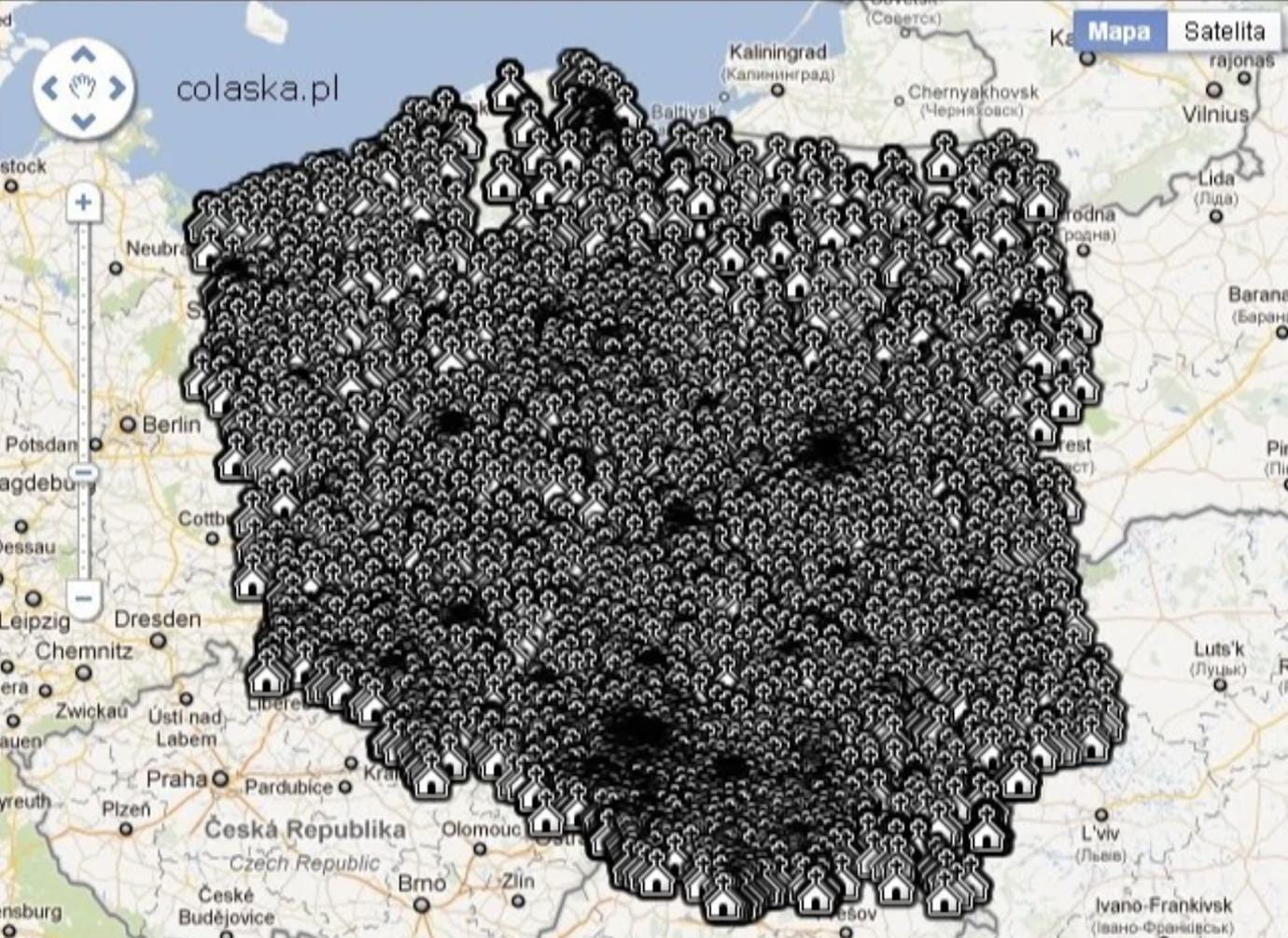

The civilisation we call the West has been underwritten by a body of texts and cultural memories from the ancient Greeks and Romans, and by the stories that make up the Bible. A vast secondary literature grew up around those scriptures, and from it emerged the sanctuary of meaning we call Christianity. I am setting aside theological questions to focus on how Christianity was established and maintained in practice, through worldly institutions.

Throughout the medieval period, the institutions of church and monarchy derived their authority from Christianity. The Catholic meaning sanctuary was understood as the word of God, mediated through His institutions. Popes, emperors, and kings were anointed in explicitly Christian rites that marked rulers as chosen by God. The symbolic work of meaning-making was carried out by clerics, monks, and theologians, a tightly knit class of intellectuals working in Latin. These were the experts of the time, and their Latin created a hard barrier between the educated class and everyone else, who lived in the vernacular.

It was, of course, messy and complicated, but overall, a level of stability was maintained through the masses’ willingness to bend a knee to the will of God and take their place within His Great Chain of Being.

The invention of the printing press around 1440 meant that books, pamphlets, and posters could be replicated relatively cheaply. Literacy spread, and through the work of Martin Luther a Bible translated from Latin into the vernacular became accessible to laypeople. Ordinary believers began to develop and circulate personal interpretations of God’s will outside the Catholic Church’s purview. As doubts grew about whether the clergy were truly best placed to interpret divine will, printed media carried reports of their worsening degeneracy. Complaints clustered around church officials selling God’s forgiveness, alongside extortion, nepotism, and sexual scandal, and the foundations of the Church’s legitimacy began to fracture.

What followed was the civilisation-wide convulsion known as the Protestant Reformation. It was an era that erupted into decades of war, waves of collective delirium, brutal persecutions, and desperate flights into new lands to build bespoke sanctuaries of meaning.

Liberal Democracy

During the Reformation the masses were unmoored from faith in their governing institutions and swung wildly between new sources of authority. They were searching for something to which they could earnestly bend a knee. As theological conflicts wreaked havoc, many turned toward more stable, observable truths, and the scientific method gained traction as a source of authority and conflict resolution.

This shift in orientation began to take explicit form in thinkers like Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), a philosopher with an idiosyncratic conception of God for his time. He understood his proto-scientific methods as a way of trying to know God, who wasn’t an omnipotent deity, but the inherent form and harmony of the material universe. Centuries later, when asked about God, Albert Einstein replied, “I believe in Spinoza’s God,” the same God many pious scientists will now admit to worshipping in the depths of a late-night, boozy conversation.

This is what Nietzsche was pointing to when he famously declared the death of God in the late 1800s. By then, God was no longer the central source of civilisational gravity around which Western civilisation conceptually clustered. In His absence, our institutions began to replace God with material reality, working hard on the enlightenment project of yoking Popper’s World’s Two and Three to his World One. The new order that emerged marked a profound reconfiguration of the West. A new paradigm of Liberal democracy emerged from the radical notion that objective truth could be found in material reality, that it’s available for all to explore, and that we all benefit from the attempt to converge on it.

Since the Enlightenment, the institutions tasked with mediating between God and the people have ceded power those claiming to mediate between the public and objective reality - universities, journalistic organisations, and government bureaucracies. Clergy gave way to experts, and material truth, not divine revelation, became the basis of their authority.

Liberal democracy became the governing logic of this post-Enlightenment order. The masses were recast as the public, and granted legal rights and protections under the rule of law. In Liberal theory, power is constrained by independent courts, competitive elections, and a pluralistic public sphere where different perspectives are permitted to clash without violence. This clash is now often framed as a metaphorical marketplace of ideas where competing claims meet in public, are tested, and either gain adoption or fade away. In the idealised story of Liberal Democracy, this quasi-Darwinian process is an engine for civilisational progress. The ideas most fit for truth and social betterment survive selection pressure and become the working assumptions of the society.

And while the process has been messy and complicated, a measure of civilisational stability has been maintained through the public’s continued willingness to bend a knee to the facts.

The Pseudo-Environment

“It is often very illuminating to ask yourself how you got at the facts on which you base your opinion. Who actually saw, heard, felt, counted, named the thing, about which you have an opinion?”

- Walter Lippmann (Public Opinion)

In 1922, a journalist by the name of Walter Lippmann published a book called Public Opinion, where he explored the limitations of the Liberal democratic order. This was a time between the world wars when innovations in radio, the telegraph, industrial printing, and cinema were making their presence felt.

Running against many of the assumptions embedded in the Liberal paradigm, Lippmann argued that people don’t have direct access to objective reality due to limitations in their knowledge and access to information. Instead, they rely on heavily mediated information and simplified constructs to create a functional but distorted version of objective reality. He called the sanctuary of meaning they inhabited a ‘pseudo-environment’.

“We are told about the world before we see it. We imagine most things before we experience them. And those preconceptions, unless education has made us acutely aware, govern deeply the whole process of perception.”

“The mass is constantly exposed to suggestion. It reads not the news, but the news with an aura of suggestion about it, indicating the line of action to be taken… Thus the ostensible leader often finds that the real leader is a powerful newspaper proprietor.”

Lippmann’s reflections on the human mind are at times cynical, but his observations about the inner workings of mass media and the manipulability of popular opinion are hard to fault. After identifying a long list of seemingly insurmountable problems with the Liberal project, Lippmann came to the conclusion we ought to abandon the marketplace of ideas in favour of a scientifically managed information environment.

“It is no longer possible to believe in the original dogma of democracy; that the knowledge needed for the management of human affairs comes up spontaneously from the human heart. Where we act on that theory we expose ourselves to self-deception, and to forms of persuasion that we cannot verify.”

Lippmann wanted to refine democracy by inserting a mediating class between events and the public mind. He assumed this class could be trained into disciplined objectivity, less prone to confirmation bias, and less dragged around by moral reflex. Their task was to study populations scientifically, then shape public opinion toward conclusions that matched the expert picture.

Lippmann wasn’t alone in his studies of mass media and meaning. The early twentieth century was a laboratory for media technique. New technologies made it possible to project a shared reality into millions of homes at once, and politics sort to engineer it. The repressive regimes that emerged in Europe and Asia are case studies of the outer limit of these techniques, when a state aims to seize total control of Lippmann’s pseudo-environment, or Popper’s World Three.

It’s comforting to treat that as a foreign pathology, but technique doesn’t respect borders. In the Liberal democracies of the West, propaganda work that began as wartime coordination and commercial tinkering evolved into the advertising and public relations industries, and have since sunk into the background of everyday life.

Throughout the mass media era, our world became awash with meticulously crafted messaging that’s designed to elicit predictable behaviours from us. The practice is so widespread that to complain about it is like yelling at a cloud. Something like the marketplace of ideas survived as a civic ideal. In practice though, an order akin to Lippmann’s vision emerged. Not explicitly as a result of Lippmann’s work, but as a function of the sheer complexity of the post industrial world.

Through a steady stream of progressive reforms, decisions that used to be fought over in elected legislatures were handed to permanent agencies and expert commissions. The rationale was meritocracy. Because the post industrial world is so complex, you need the most competent people to be insulated from the heat of politics to keep the machine running. Sophisticated public relations techniques are then used to sell their prescriptions to the masses, and a fairly narrow Overton window was maintained by media institutions.

Our symbolic work of meaning making was carried out by analysts, academics, bureaucrats, and media professionals; a tightly knit class of reality interpreters who often work in technical dialects. Seen this way, the modern knowledge class can resemble a secular echo of the premodern clerisy. The level of actually existing Liberal democracy each nation can claim to have rests on this class’s openness to heterodox debate, and its eagerness to gauge ground-level public opinion.

The Digital Reformation

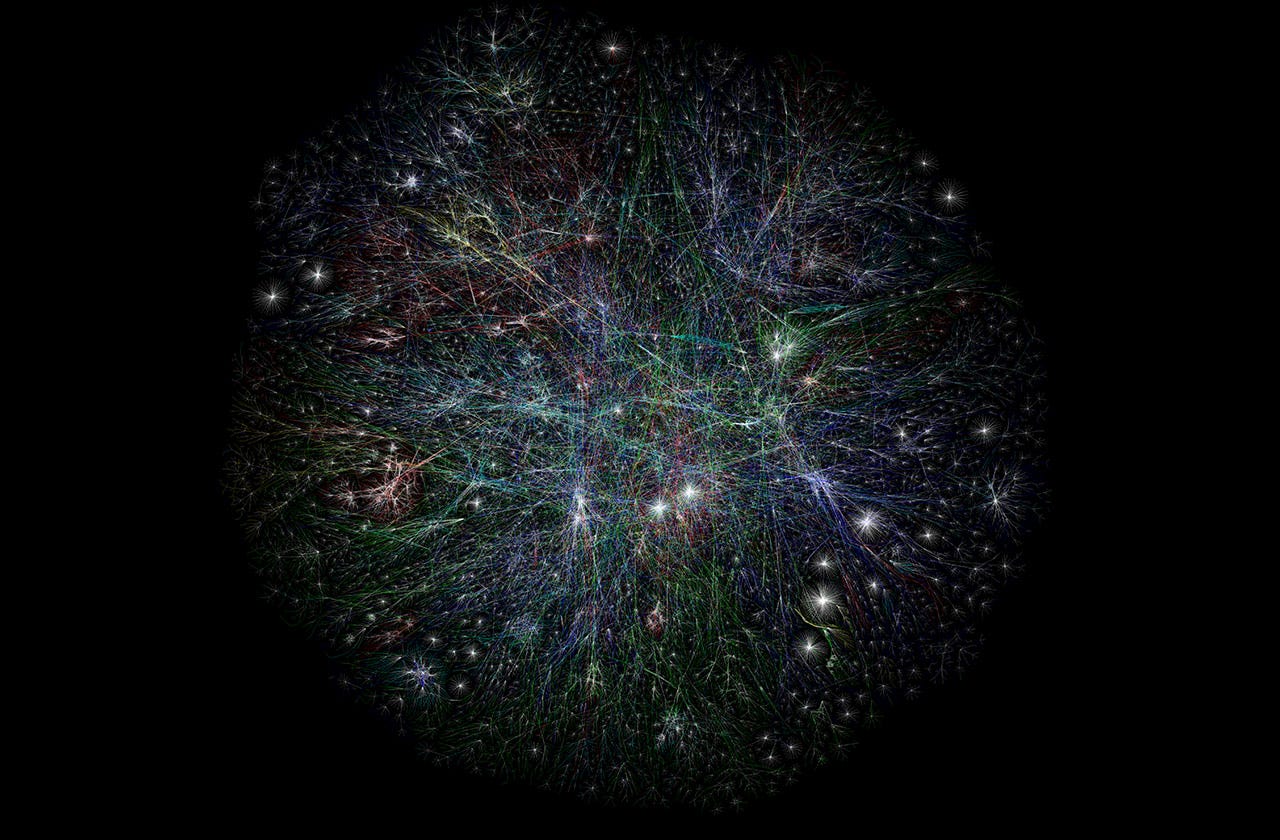

When the enormous media distribution channels of the Internet opened up at the turn of the 21st century, we effectively created a user interface into World Three. Anyone with a PC and web connection could have their ideas frictionlessly replicated across millions of screens worldwide.

Institutional floodgates began to crack open a tsunami of information and perspectives rushed into our shared world of meaning. If history never repeats itself but often rhymes, then the invention of the printing press and the advent of the Internet share a particular ring. They both increase information flows by orders of magnitude and facilitate meaning-making outside the purview of intermediary institutions.

Consider that before the flood, if your ideas were unpalatable or incoherent to the people employed by academic, media, arts, and religious institutions, they wouldn’t be circulated in an impactful way. In theory, you could still participate in the marketplace of ideas, but you’d be stuck trying to distribute leaflets or magazines on a small scale, perhaps handing out CDs on a street corner or ranting from a soapbox. Whether you’re excited by the possibilities of mass participation in mass media or lament the loss of the knowledge class filters, the old establishment did function to make the world a more coherent place.

The information floodplains we now inhabit have a hallucinatory feel, as if any sense of shared reality has come unstuck. Our human need to create sanctuaries of meaning compels like-minded people to form digital networks around bespoke World Three configurations, generating vast amounts of mental material in ways that are faster and cheaper than ever before possible. These networks interpret and arrange objective facts in different ways and fight for the legitimacy of their unique perspectives. In an environment awash with perspectives and uncertainty, a simple and emotionally resonant interpretive framework becomes appealing, and ideology is a means for cutting through complexity and coordinating amidst the noise.

In this new information landscape, complaints cluster and coalesce into political movements faster than defensive public relations strategies can be deployed. The knowledge class are rapidly abandoning the marketplace of ideas civic ideal for pragmatic censorship measures. Left and right populism, political entertainment, and ideology prevail as new forms of swarm propaganda are developed by powerful interests in realtime.

For better or worse, we’re at the beginning of a civilisational convulsion on the scale of the Protestant Reformation.

Your substack is criminally underrated.

This is maybe the best thing I've read online - it's at least in the top five. I've been an "internet person" since 1994. I have lived half of my life online and half off-line. I know what the internet was before social media and what it became afterwards. So much of what we're living through now is the fight for control of this new territory, not unlike when the Puritans sailed to the new world or the westward expansion. We're doing the same thing only now it's in the virtual space. Imagine what it would be if we could ever get off this planet and colonize others. I didn't see this mess coming. I was securely in my own bubble online. I have a Gen-Z daughter who was ground zero in the Tumblr fanaticism that grew the roots for the Woketopia. But I guess I never imagined so much power would be handed over to the Left. My former side used to be the side that was the counterculture, the rebels, the discards, the upstarts. To see the rise of totalitarianism on the LEFT is what continues to blow my mind. I know it isn't as simple as left or right.

World III is like the "habitus" that forms our reality. Before Musk bought Twitter that was decided by the blue-checks, the media and the Democrats who all formed a fascist-like alignment of power that allowed them complete control over our shared reality. That's what we seem to be at war about now. Who gets to decide that?

For people like my daughter, she doesn't know any other way of life. But I remember life before. That is why it bothers me so much. Anyway, thanks for this.